The Relationship Between Perspective-taking, Lie Detection and Self-construal Among Taiwanese

Dublin Core

Title

The Relationship Between Perspective-taking, Lie Detection and Self-construal Among Taiwanese

Creator

Wen-Hsuan (Macy) Su

Date

2018

Description

“Theory of Mind” (ToM) refers to an ability, which allows us to understand what other people may believe, think, know, feel. Also, ToM is considered to play an essential role in social interaction. Evidence suggests that improved ability to understand others’ mental states through training can also improve our ability to generate lies and understand what kind of situations people may lie. In addition, previous studies point that there are differences in lie-telling and perspective-taking between individualistic and collectivist cultures. Therefore, the current study aimed to investigate whether there is a relationship between the perspective-taking, lie detection and self-construal (individualism and collectivism). Data were collected from 40 typically developed adults in Taiwan (M = 23.98, SD = 2.99). Each participant was asked to complete three computer-based tasks, namely a perspective-taking task; a lie detection task, and a questionnaire of Auckland Individualism and Collectivism scale (AICS). The result showed that there is no relationship between the ability of perspective-taking and lie detection. Also, the people scored higher individualism will show better performance on pointing out truths, but worse on detecting lies. It might relate to the “truth bias”, which means that people will typically assume or believe others are telling truths rather than lies, especially distinguishing on individualists. However, because cultural effects such as language differences and self-construal might affect individuals’ performances on instances of ToM use, the current study suggests that people might need to use different cues to detect lies in a truth-versus-lie judgment between different cultures.

Subject

None

Source

Participants

Data were collected from 40 typically developing adults from an opportunity sample in Taiwan. The entire group was composed of 20 males and 20 females between the ages of 18 and 30 (M = 23.98, SD = 2.99). All participants stated that they were Taiwanese, speaking Chinese/Taiwanese Mandarin as their first language, with normal vision or vision which had been corrected to normal. All of the participants had not been diagnosed with any neurological or developmental disorders. The data of participant No.40 was excluded from analyses because the participant only responded with the same positive answer to each question in the lie detection task.

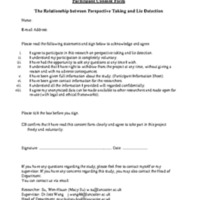

The original minimum required sample size was 44, which was determined a priori by using G*Power software. This number was calculated based on assuming a medium effect size of 0.4 and a reasonable power of 0.8. However, 40 was considered as a more suitable sample size, as the experiment consisted of two orders for the perspective-taking task, four sub-sets of the lie detection task and a questionnaire. In order to counterbalance stimuli presentation, the target sample was set to 40, as it is a multiple of eight (two times four times one); it is also the closest number to 44. All participants had been given the consent form and the information sheet to understand the contents of the project before the tests began. Furthermore, this project was approved by the ethics process from the Department of Psychology at Lancaster University.

Design and Procedure

Each participant was asked to complete three computer-based tasks, namely, the perspective taking task, the lie detection task, and a questionnaire of the Auckland Individualism and Collectivism Scale (AICS). All of the tasks were translated or designed in the participants’ first language, in this case, Chinese/Taiwanese Mandarin. All of the tasks were presented on a laptop and participants responded by using the computer mouse. The full session took around an hour in total.

Perspective-taking Task

The original perspective-taking task was called the “director task”, which can be traced back to the studies from Keysar et al. (2000) and Apperly et al. (2010). The present study employed a similar version of the director task which was presented in the study from Wang et al. (2016). In the instruction of the perspective-taking task, participants were given a demonstration of how to use a computer mouse to select and move the object. Later, the experimenter explained to participants that the speaker/director was standing behind the shelf and would not be able to see the objects in the blocked slots. It was impossible for the speaker/director to ask participants to move the object which was in the blocked slot (see Figure 1). Participants were asked to consider the speaker/director’s perspective and respond as quickly and accurately as possible.

Participants had a chance to practice (6 trials) and ask questions before the start of the task. The task was divided into four blocks, and participants were allowed to take breaks between each block. There were a total 128 trials in the task, 16 of which corresponded to the experimental trials; the other 16 corresponded to the control trials and the rest were fillers. The fillers were regarded as a baseline measure for the non-perspective taking aspect of the task, such as understanding and identifying the speaker/director’s instructions. In 16 of the experimental trials, there were differences between the speaker/director’s description and the participants’ point of view. In contrast, the control trials provided a close match in terms of visual and audio stimuli, but the control trials did not impose the demand to perspective-taking. For example, as can be seen in the right-hand picture in Figure 1, if the speaker/director ask participants to move the “bigger” balloon to take the speaker/director’s perspective, participants should move the yellow balloon rather than the pink one, which was the bigger balloon from the participants’ own perspective. By the end of the task, only the number of egocentric errors committed on experimental trials were counted; the errors reflect failure to account for the director’s perspective.

Figure 1. Left: An example of the control trials. Right: An example of the experimental trials.

Lie Detection Task

Participants were asked to watch 16 videos (each video lasting around 15~45 seconds). The videos were recorded by four volunteer models from Lancaster University. All models were Taiwanese and spoke Chinese/Taiwanese Mandarin as their first language. Each model recorded 16 videos in total which comprised four stories. Each story contained to two truths and two lies, from a first person and a third person perspective for each story (there are four versions of each story). For the story contents, there were several elements that storytellers were required to include in their stories (see Appendix A). In addition, the storytellers were given two designated elements to lie about in the lie stories.

There was a total of 64 videos. The videos were evenly and pseudo-randomly divided into four lists. For example, participants never watched two videos of the same storylines containing lies and told from a same perspective by different storytellers in one list. Therefore, each list contained 16 unique videos. Participants watched videos from one of the lists, and at the end of each video, they were asked to identify whether they thought that the storytellers were telling a truth or a lie. To make sure the participants would concentrate on watching videos rather than just guess the answers, participants were asked a question about an aspect of each video. The questions were used as inclusion criteria, whereby only correct responses of the aspects were included in the data analysis.

Auckland Individualism and Collectivism Scale (AICS)

The third test used was the Auckland Individualism and Collectivism scale (AICS), which was developed by Shulruf, Hattie and Dixon (2007) and was used to measure individuals’ self-construal, namely, individualism and collectivism. The questionnaire consists of 30 questions (see Appendix B and C), which includes three dimensions of individualism and two dimensions of collectivism. For individualism, the scale consists of 12 items and is divided into three dimensions, namely, responsibility, uniqueness, and competitiveness. For collectivism, the scale consists of 8 items, and two dimensions are referred to: advice and harmony. Each of the dimensions was composed of four items. The questionnaire was presented in an online form, and participants were asked to complete it after they had finished the lie detection task. The response to each question was scored using a six-point likert scale from 0 (Never) to 5 (Always). The maximum score in the individualism trial was 60, and the maximum score in the collectivism trial was 40. A higher score on each of the trials indicated that an individual was more inclined to individualism or collectivism.

The AICS questionnaire has been shown to work in different cultures such as the United Kingdom, China, Romania and Italy (Bradford et al., 2018; Ewerlin, 2013). This means that this questionnaire can be used as a feasible measure in both individualistic and collectivistic cultures. Previous studies have mentioned that an individual can simultaneously show tendencies towards both individualism and collectivism; in other words, an individual may be able to achieve a high or low score on both subscales (Bradford et al., 2018; Shulruf et al., 2011). With this in mind, the analysis of the current study did not divide participants into two groups for individualism and collectivism. Instead, this study used the AICS questionnaire to obtain participants’ scores in individualism and collectivism, and to observe the relationship between individuals' self-construal and their ability to detect lies.

Data were collected from 40 typically developing adults from an opportunity sample in Taiwan. The entire group was composed of 20 males and 20 females between the ages of 18 and 30 (M = 23.98, SD = 2.99). All participants stated that they were Taiwanese, speaking Chinese/Taiwanese Mandarin as their first language, with normal vision or vision which had been corrected to normal. All of the participants had not been diagnosed with any neurological or developmental disorders. The data of participant No.40 was excluded from analyses because the participant only responded with the same positive answer to each question in the lie detection task.

The original minimum required sample size was 44, which was determined a priori by using G*Power software. This number was calculated based on assuming a medium effect size of 0.4 and a reasonable power of 0.8. However, 40 was considered as a more suitable sample size, as the experiment consisted of two orders for the perspective-taking task, four sub-sets of the lie detection task and a questionnaire. In order to counterbalance stimuli presentation, the target sample was set to 40, as it is a multiple of eight (two times four times one); it is also the closest number to 44. All participants had been given the consent form and the information sheet to understand the contents of the project before the tests began. Furthermore, this project was approved by the ethics process from the Department of Psychology at Lancaster University.

Design and Procedure

Each participant was asked to complete three computer-based tasks, namely, the perspective taking task, the lie detection task, and a questionnaire of the Auckland Individualism and Collectivism Scale (AICS). All of the tasks were translated or designed in the participants’ first language, in this case, Chinese/Taiwanese Mandarin. All of the tasks were presented on a laptop and participants responded by using the computer mouse. The full session took around an hour in total.

Perspective-taking Task

The original perspective-taking task was called the “director task”, which can be traced back to the studies from Keysar et al. (2000) and Apperly et al. (2010). The present study employed a similar version of the director task which was presented in the study from Wang et al. (2016). In the instruction of the perspective-taking task, participants were given a demonstration of how to use a computer mouse to select and move the object. Later, the experimenter explained to participants that the speaker/director was standing behind the shelf and would not be able to see the objects in the blocked slots. It was impossible for the speaker/director to ask participants to move the object which was in the blocked slot (see Figure 1). Participants were asked to consider the speaker/director’s perspective and respond as quickly and accurately as possible.

Participants had a chance to practice (6 trials) and ask questions before the start of the task. The task was divided into four blocks, and participants were allowed to take breaks between each block. There were a total 128 trials in the task, 16 of which corresponded to the experimental trials; the other 16 corresponded to the control trials and the rest were fillers. The fillers were regarded as a baseline measure for the non-perspective taking aspect of the task, such as understanding and identifying the speaker/director’s instructions. In 16 of the experimental trials, there were differences between the speaker/director’s description and the participants’ point of view. In contrast, the control trials provided a close match in terms of visual and audio stimuli, but the control trials did not impose the demand to perspective-taking. For example, as can be seen in the right-hand picture in Figure 1, if the speaker/director ask participants to move the “bigger” balloon to take the speaker/director’s perspective, participants should move the yellow balloon rather than the pink one, which was the bigger balloon from the participants’ own perspective. By the end of the task, only the number of egocentric errors committed on experimental trials were counted; the errors reflect failure to account for the director’s perspective.

Figure 1. Left: An example of the control trials. Right: An example of the experimental trials.

Lie Detection Task

Participants were asked to watch 16 videos (each video lasting around 15~45 seconds). The videos were recorded by four volunteer models from Lancaster University. All models were Taiwanese and spoke Chinese/Taiwanese Mandarin as their first language. Each model recorded 16 videos in total which comprised four stories. Each story contained to two truths and two lies, from a first person and a third person perspective for each story (there are four versions of each story). For the story contents, there were several elements that storytellers were required to include in their stories (see Appendix A). In addition, the storytellers were given two designated elements to lie about in the lie stories.

There was a total of 64 videos. The videos were evenly and pseudo-randomly divided into four lists. For example, participants never watched two videos of the same storylines containing lies and told from a same perspective by different storytellers in one list. Therefore, each list contained 16 unique videos. Participants watched videos from one of the lists, and at the end of each video, they were asked to identify whether they thought that the storytellers were telling a truth or a lie. To make sure the participants would concentrate on watching videos rather than just guess the answers, participants were asked a question about an aspect of each video. The questions were used as inclusion criteria, whereby only correct responses of the aspects were included in the data analysis.

Auckland Individualism and Collectivism Scale (AICS)

The third test used was the Auckland Individualism and Collectivism scale (AICS), which was developed by Shulruf, Hattie and Dixon (2007) and was used to measure individuals’ self-construal, namely, individualism and collectivism. The questionnaire consists of 30 questions (see Appendix B and C), which includes three dimensions of individualism and two dimensions of collectivism. For individualism, the scale consists of 12 items and is divided into three dimensions, namely, responsibility, uniqueness, and competitiveness. For collectivism, the scale consists of 8 items, and two dimensions are referred to: advice and harmony. Each of the dimensions was composed of four items. The questionnaire was presented in an online form, and participants were asked to complete it after they had finished the lie detection task. The response to each question was scored using a six-point likert scale from 0 (Never) to 5 (Always). The maximum score in the individualism trial was 60, and the maximum score in the collectivism trial was 40. A higher score on each of the trials indicated that an individual was more inclined to individualism or collectivism.

The AICS questionnaire has been shown to work in different cultures such as the United Kingdom, China, Romania and Italy (Bradford et al., 2018; Ewerlin, 2013). This means that this questionnaire can be used as a feasible measure in both individualistic and collectivistic cultures. Previous studies have mentioned that an individual can simultaneously show tendencies towards both individualism and collectivism; in other words, an individual may be able to achieve a high or low score on both subscales (Bradford et al., 2018; Shulruf et al., 2011). With this in mind, the analysis of the current study did not divide participants into two groups for individualism and collectivism. Instead, this study used the AICS questionnaire to obtain participants’ scores in individualism and collectivism, and to observe the relationship between individuals' self-construal and their ability to detect lies.

Publisher

Lancaster University

Format

Data/Excel.xslx

Identifier

Su2018

Contributor

Rebecca James

Rights

Open

Relation

None

Language

English

Type

Data

Coverage

LA1 4YF

LUSTRE

Supervisor

Jessica Wang

Project Level

MSc

Topic

Cognitive, developmental

Sample Size

40 typically developing adults

Statistical Analysis Type

Regression, t-test

Files

Collection

Citation

Wen-Hsuan (Macy) Su, “The Relationship Between Perspective-taking, Lie Detection and Self-construal Among Taiwanese,” LUSTRE, accessed May 3, 2024, https://www.johnntowse.com/LUSTRE/items/show/96.